The Challenge

A big question for 3D bioprinting is in what avenues can it become more mainstream, more of an everyday technology used in a workflow?

While it can certainly be found in several research labs around the world with scientists changing slight variables to create new data to publish, its value impact in direct human development has been more limited. Its promise to be fulfilled.

Organ engineering has been popularized repeatedly on the mainstream media as an endpoint for bioprinting. Its younger sibling, which is no less exciting, would be the ability to accelerate drug discovery by creating models that accurately represent a specific organ or diseased function in humans.

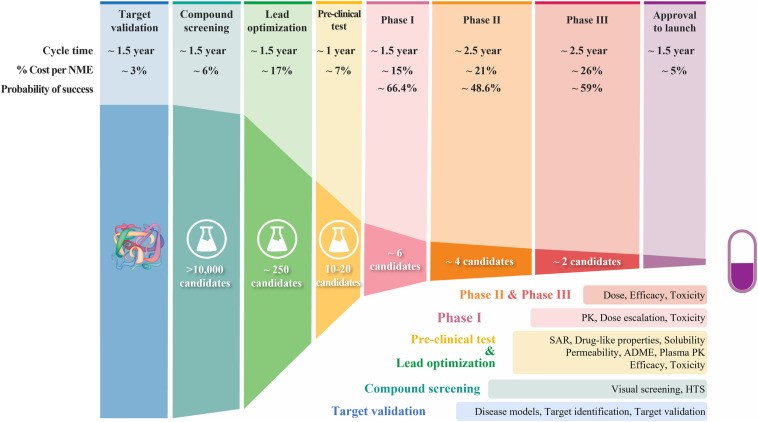

The reason it would be exciting is since the cost and time to bring a drug to market is 10-15 years and ~2 billion dollars. Take this infographic from Dr. Sun’s paper on “Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it?”

Most drugs fail in Phase I, II, or III, the most expensive phases, given they lack clinical efficacy or they don’t pass safety albeit they passed this safety in all 6 years of the phases before. That’s specifically due to the fact that most of those lead optimization and pre-clinical test are done on either 2D cell cultures or animal models. Both of which don’t have accurate correlation to the real human 3D body.

So, what if a 3D bioprinted model could be made that would have greater accuracy to how the human body would behave?

It’s a great promise and a similar promise to what the organ-on-chip community is trying to figure out.

There are two real challenges that are causing the barriers: the biological and the economical

The Biological

For the bioprinting community, great engineering achievements have been made in mechatronics with printers, and biomaterial chemistry control to achieve beautiful structures in vitro. Some that come to mind are the perfused lattice structures created from Jennifer Lewis’s lab, the beautiful liver design made by Volumetric and Jordan Miller, or the impressive cardiovascular scaffolds from FluidForm and Adam Feinberg. These have all been true feats for the field.

The only fall back is that the bioprinting community ultimately has to be at the service of the biological community, particularly in this case, the drug developers. And drug developers are not wowed by works of scaffold art or even cellular viability. Biologist dive deep into the heart of cells, they are specific about what they study. True microeconomist studying the specifics of their disease, whether it’s their sequence data, proteomics output, or specific cell-expression markers. And the reality is to study a specific disease or specific biological output takes time and patience.

So, if the question is biological, then we ask how can basic 3D bioprinters create cellular arrangements that lead to unseen, unique biological outputs that would be of interests to study safety or disease specific markers?

Some examples to name a few are Jennifer Lewis unique cell growth from kidney cells when printed in tubule structures, Shrike Yu Zhang demonstrated increased beating of heart cells when patterned in lines using a bioprinter, or how Mark Ferrer showed vascularized printed skin models exhibit correct cell markers when compared with real skin models.

And that’s always the trick, how can by adding patterns or 3D we compare to what’s actually happening in humans in a more accurate way.

One industry that is more developed than bioprinting, yet has understood the ability to add in geometry to get unique biological outputs is the organ-on-chip industry. One of the most notable company’s is EmulateBio.

The Economical

Emulate Bio has done some tremendous scientific work in showing how cellular orientation and 3D interaction play a direct role on better mimicking the human body. Their flagship lung-on-chip was able to mimic how toxic particles can be caught in its 3D model but not in a 2D model. Likewise, their liver-on-chip showed how human’s can digest a specific drug, while rat livers can’t. Overall, they have 6 chips all backed by really in-depth detailed science.

While the scientific papers corresponding to each model have been works of art and years of dedication, after 30 years, their ability to disrupt the drug development market has been much slower than what was originally anticipated. Yes, the initiatives by governments to limit animal testing is helping the organ-on-chip adoption. Yet, the growth has been mildly if even any disruptive to animal models.

The problem really lies in, yes animal models are still around, but the true problem is more so the number of models ordered by pharma for preclinical studies and the prices they are willing to pay for them. If you scroll back up to the chart, you can notice that pre-clinical test are only around 10–15 models, and 250 for lead optimizations.

Animal model companies have hundreds of different models and ordered by almost all drug companies to get a reference point to data that has come in the past. Organ-on-chip companies have a limited number of models and they have spent years developing them. Once finished, they then sell them as a premium equivalent to animal models to drug companies. Their uniqueness and impact are arguably being undervalued. And the reason is most pharma wants to treat it as just another data point within their mix of models to get indications if they are heading in the right direction. It’s probably also hard to sell an animal model replacement at a much higher price than animal models, if not the greater pharma community wouldn’t want to pay for them.

So, what’s happening? Well, there is this group of companies who have received a substantial amount of investment to develop these sophisticated organ-a-chip, tissue-on-chip, or body-on-chip applications to then only be considered and paid as a premium animal model and used in certain disease development targets. And given this dynamic, the initial ROI of these investments are coming into question.

So, what’s the solution? One company in particular stands out, HemoShear Therapeutics.

The Solution

Before HemoShear Therapuetics, there was HemoShear. And HemoShear had developed a unique platform that would provide unseen biological outputs from liver cells given how they created a 3D force on the cells. They initially tried selling this model to pharma company’s who were excited about the idea of getting a so-called premium animal model to test for certain applications.

In realizing the challenge of wide adoption, market penetration, and business viability, HemoShear pivoted to boldly attempt to try and make their own drug pipeline. And this move fundamentally changed the way how they saw their own platform. It went from being a premium animal model, to a highly competitive screening, optimization, and testing platform that they could optimize for certain diseases and receive leading edge outputs.

That strategic shift of how they valued their own platform propelled them to become more coveted as a partner and Takeda took notice. Takeda offered potential milestone payments of $470 million and royalties if successful. It’s a big win for 3D biology and while still no drug is on the market for the partnership, they continue to work towards it with full steam ahead.

The Take Away

3D complex biology platforms have tremendous value to offer. The way this value is offered is extremely important. It will take much longer to go head-to-head with animal models to create disruption given how extensive it is to develop these complex models. It has to be done with the finesse of Emulate Bio, but by taking a HemoShear Theraputics approach to view the platform as the catalyst for the drug pipeline itself on a specific disease. This will lead to many more wins and more valuable drugs coming to market faster, at a cheaper price albeit doing more heavy lifting up front. So while not easy, either make drugs on your own platform or sell the platform in return to be a full partner on the royalties. That’s where the ROI will be for now.

Some thoughts,

Leave a comment