The historical overpromise of bioprinting

For many years, the media and the public have enjoyed to speculate on the possibilities of making implantable organs. This has been particularly driven by certain showings in the media. While good to show dreams, sometimes have given to much promise to soon. For those in the industry, we can think about Dr. Vacanti’s ear on the mouse, Dr. Anthony Atala’s kidney on TED, and more recently now the Dr. Martine Rothblatt’s 3D printed lung on the LIFE TISELF stage.

These portals of the future are healthy, giving imagination to the possibilities we can achieve, yet logically it’s falling out of the natural innovation continuum. Particularly many stepwise developments are being skipped. Great inventions have a time and place in history and they have foundations of things that came before them. The lightbulb, the combustible engine, the computer, or the internet all were born because humanity had paved the foundation for many pieces to come together to make a small leap at that time. Now over many years, those small leaps incrementally appear as big leaps. The same idea will hold true for the dawn of the leap of the printed organ. We are many steps removed from what would ultimately be what Atala or Rothblatt display. Yet question comes then, what is the next step? Where are we in the series?

Looking to materials already implanted

There are a few companies that we could highlight who small chiseling steps are poised to make big impacts in the lives of people. And the place they started was simply looking at materials they could further control yet were already being implanted in the body without geometry.

Dimension Inx was company founded by Dr. Adam Jakus as a spin out of Dr. Ramille Shah’s lab from Northwestern University in Chicago. Their most notable publication that started their endeavor dates back to 2016, “Hyperelastic bone : a highly versatile, growth factor-free osteoregenerative, scalable, and surgically friendly biomaterial.” In the paper they describe, how they had been observing the frequent use of synthetic hydroxyapatite as bone fillers. These fillers were being used as putties, injectables or granules to pack into surgical sites to treat bone defects. The limitation with these processes were that they didn’t have any porosity, think there was just this material that was being packed into a bone hole. This limits how much bone and blood vessels can grow into it. The key thing here though is that these injectable products were on the market, approved by the FDA, and having some benefit. The question though was, what if they could 3D print them to provide lattice structures that would significantly improve their performance?

That correct question, led them to think about how others were attempting to add in lattice structure to these materials. They then cleverly invented a method to extrude these materials with solvents that would evaporate. Their initial success of showing a material that had similar chemical properties to products that were on the market, yet was 3D printable, chemically compliant, mechanically sounds, and bioactive has been the foundation to their current success.

They have remained persistent and at the time of this writing they achieved, their 510k FDA clearance last December in 2022, and more recently had their first ever patient transplantation. This product is not printed with cells, has no designed blood vessels, or highly complex geometries. Its simply taken a step of innovation, of adding in lattices by ingeniously 3D printing materials already approved. And their product is poised to help many people who are in need of bone in growth for bone defects.

The 2nd company to take a look at would be the rise of Beacon Bio, now a part of Desktop Health after acquiring it back in 2021. Beacon Bio was started by Dr. Nicole Black out of Jennifer Lewis’s Lab at Harvard in collaboration with Dr. Aaron Remenschneider, a pediatric ENT at Boston Children’s Hospital. They first saw a large need in the ability to repair perforated eardrums. Today the standard is to take autologous tissue grafts from the perforation site in the ear. The challenge is these tissues do not degrade or remodel leaving subpar eardrum performance as well as potential scarring or infections at the graft sites.

So, the question began, how can a better solution be created? They began with design requirements. The device should have a relevant thickness, biodegradable, biocompatible, and have different sizes. Particularly it should have anisotropy to guide cell alignment. That idea to add in anisotropy is something particularly relevant to 3D printing. Anisotropy basically means that the fibers that get created have to have directionality, and not only that but one layer should have one direction and the one below should have a different direction.

The next and this probably the most important step was they looked at the FDA Safety Summaries for materials that have already been used in other medical devices. Their flagship product PhonoGraft is made using P-PEUU which is a polyurethane polymer with polyethylene glycol (PEG) included to add for degradation properties, which was recently described in Nicole’s keynote at the BioMED Boston conference. It seems to have taken several iterations to come to their final design as it differs from the formulations tried out in the initial study that really kicked off the project and the idea. Yet, polyurethanes are commonly used in several other medical devices such as catheters and polyethylene glycol (PEG) is used in pharma.

They are now working their way through the FDA, which as of an article in July of 2023 states that the PhonoGraft is eligible for the 510(k) pathway. A large part of their success to date with the FDA can be argued that Beacon Bio has taken materials that have already been used in the body, and have added in the step of 3D printing. It seems they took a few more steps in combining innovation though like adding in a novel design for improved implantation, and the FDA surprised them to see a small human study. So, the balance of innovation needs to be addressed. Adding in geometry with current materials approved, but understanding the limitation in adding too many novelties like a new implantation design might increase the risk of time and cost needed to bring a product to market. The earlier the discussions with the FDA, always the better, as Black stated in her presentation.

The perspective of innovation in today’s world driven by venture capital funds

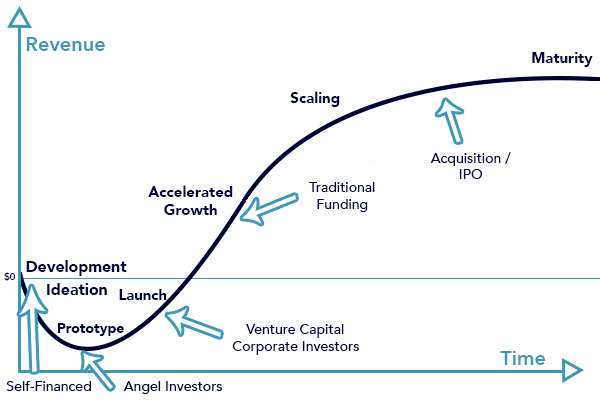

One of the specific reasons for the importance in the stepwise approach, this idea of adding in geometry to already approved materials is because the time horizon from idea conception to successful commercialization is a long one, on the order of about 10 years. Look at the image below by dnb.com

The competing aspect to that is the roughly 10-year horizon to venture capital fund timelines. It is debatable, but in today’s current environment startups by enlarge are funded through venture capital. Yes, startups can get off the ground with government grants, which particularly helps in the earlier years, but once venture funds are taken by founders a clock starts. Investors have limited partners of whom they have to return capital to once the fund lifespan is up, with a return on that investment.

Whitney Harring-Smith, from Anzu Partners, explains this in one of his most recent blogs FWIW. Cap tables can get complex, but venture investors have a date and a percent return on their minds as to when they need to see the investment liquidated. Venture funds have a life span, a vintage as he says, and therefore the clock is ticking.

What this means for the company is that the risk of product development has to be managed. An innovation has to be progressive, forward moving, and disruptive enough where it merits a 10-year investment by individual’s lives, resources, and development. Yet, the complexity can’t be too high where the innovation needs more than 10 years to be a commercializable product. Picking the right fund is key, some funds can go longer than this and we can get into that in another story, but most funds lives are around 10-years. And if the clock is up, the investors might favor liquidating the company’s assets versus seeing the innovation through themselves, which brings complexity to the product’s maturation.

The takeaway: find the sweet spot

That sweet spot in the context of what we’ve explored above in 3D printing, is taking some of these approved materials, and configuring them into new geometries given new 3D design freedoms. Not printing with cells yet, or having multimaterial prints, or highly complex internal architectures. Just the simple addition of geometries, such as lattices or lines, applied in a unique way to a specific disease or problems. And while this is less hype worthy than a company coming out to say they will print organs; these stepwise innovations are having tremendous impact on people’s live and are creating a large amount of value for shareholders. This is the type of stories we should be getting exciting about and look forward to seeing the number of these wins rising. As this will ultimately help us then get to those truly breakthrough continuums endpoints, like bioprinted tissues with cells and vasculature.

Leave a comment