3D printing has come a long way since its beginnings, but the field is still rapidly evolving. A new technique called Dynamic Interface Printing (DIP) recently published in Nature brings a fresh approach to printing complex, centimeter-sized 3D structures in mere seconds. This technique has broad implications for industries like healthcare, aerospace, and bioprinting, where there’s a demand for intricate designs and fast production. Live video can be seen here.

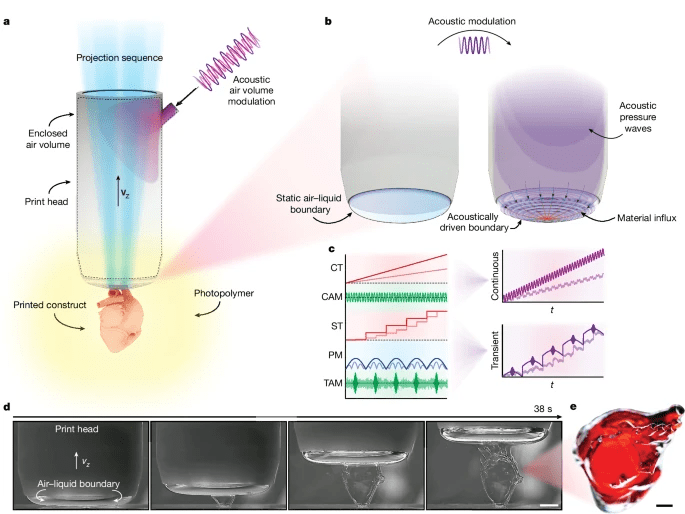

Figure 1. In Dynamic Interface Printing (DIP), an air–liquid boundary is created at the bottom of a print head partially submerged in a photopolymer solution. This boundary serves as the printing surface, where projected patterns solidify the material. Acoustic control of the air pressure within the print head enhances material flow through capillary waves. DIP operates in two modes: a continuous mode, where the print head and acoustic modulation move steadily, and a transient mode, where steps in translation, pressure adjustments, and acoustic pulses adjust the interface. This setup enables rapid, detailed 3D printing, shown in time-lapse images of a heart structure printed in under 40 seconds.

What Is Dynamic Interface Printing?

Dynamic Interface Printing (DIP) stands out because it uses a unique, acoustically modulated air–liquid boundary as the printing “interface.” Most traditional 3D printing techniques use a solid surface or resin, which prints objects layer by layer. However, DIP uses a meniscus (the curved surface formed by the liquid) at the end of a submerged print head, allowing it to create structures directly in the liquid. A light source from above solidifies patterns at this boundary, which helps shape each part quickly and with great detail.

Unlike typical layer-by-layer printing methods, DIP doesn’t require complex optics, special chemicals, or an intricate setup to achieve high precision. This simplicity is an advantage, especially in biofabrication, where materials like hydrogels, which mimic the properties of biological tissues, are challenging to handle with conventional printers.

Why DIP Matters for 3D Printing and Bioprinting

Speed and simplicity are two key aspects that make DIP so exciting. Traditional printing techniques take hours to create structures with similar complexity, but DIP accomplishes this within seconds. Its ability to print complex shapes without the need for physical supports makes it possible to create detailed models that would be tough to produce otherwise.

For bioprinting, this innovation is particularly promising. Since DIP can print soft materials compatible with living cells, it opens doors for tissue engineering and the creation of custom medical implants. The ability to print at high speeds with excellent resolution means DIP could be used to develop real-time models or create custom structures for patients on the spot, with minimal cell damage—an essential requirement for bioprinting applications.

How DIP Stacks Up Against Other Technologies

DIP has a few standout features:

- Acoustic Modulation: This is where DIP’s print head vibrates to form tiny waves at the liquid surface. These waves improve material flow, which helps in maintaining the printing speed and resolution across different material types.

- Container Flexibility: Unlike other printing systems that require specialized containers or transparent walls, DIP is adaptable to many setups, which makes it versatile for various materials, from plastics to hydrogels with cells.

- Fast, High-Resolution Production: The rapid print times are enabled by controlling the meniscus through pressure changes and light patterns. This efficiency is especially advantageous for prototyping and manufacturing in industries where time and precision are critical.

By creating smooth, detailed structures without complex adjustments, DIP is a powerful tool that addresses many of the limitations of 3D printing, making it easier to incorporate into different workflows and applications.

The original publication can be found here. This work was lead by Dr. David Collins from the University of Melbourne

Leave a comment