The promise of printing fully functional, immune-matched human organs has long been a defining ambition of regenerative medicine. Now, that ambition is moving from theory to large-scale execution.

This week, Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), announced the first awardees of its ambitious Personalized Regenerative Immunocompetent Nanotechnology Tissue (PRINT) program—a five-year, up-to-$176.8 million initiative aimed at producing on-demand, immune-compatible human organs.

If successful, PRINT could redefine transplantation by eliminating chronic organ shortages, reducing waitlists, and removing the need for lifelong immunosuppressive drugs.

Why PRINT Matters

Today, tens of thousands of patients in the United States wait years for donor organs. Many never receive one. Even for those who do, the outcome is often imperfect: transplanted organs typically last 15–23 years and require continuous immunosuppression, bringing high costs and serious side effects.

Shortages are driven by:

- Limited donor availability

- Geographic disparities

- Strict blood-type and tissue-matching requirements

- Low organ donation rates

PRINT’s core vision is innovative: instead of waiting for donors, patients could receive organs fabricated within hours using their own cells—or cells from curated biobanks—engineered to avoid immune rejection.

According to ARPA-H Director Alicia Jackson, the goal is nothing less than a structural reset of transplant medicine.

The Technical Moonshot

To succeed, PRINT teams must solve challenges that have stalled tissue engineering for decades:

- Printing human-scale organs (not millimeter-scale constructs)

- Integrating dense, perfusable vascular networks

- Supporting long-term cell survival and maturation

- Establishing functional biliary, filtration, and metabolic systems

- Scaling cell manufacturing and bioreactor platforms

Program Manager Ryan Spitler describes the effort as “extraordinarily hard,” requiring coordinated breakthroughs in bioprinting hardware, biomaterials, cell sourcing, and bioprocess engineering.

In practical terms, PRINT is pushing bioprinting from research prototypes toward regulated, transplant-ready manufacturing systems.

Who’s Building the Future of Printed Organs?

ARPA-H selected five leading academic centers to anchor the program’s first phase.

🧬 Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, PA

CMU is developing an “immune-silent” bioprinted liver aimed at first-in-human trials within five years. The focus is on cost-effective production and early deployment for acute liver failure, with long-term expansion to chronic disease.

🩺 Wake Forest University

Winston-Salem, NC

Wake Forest is building vascularized renal tissue to augment kidney function. The team is pairing preclinical validation with early commercialization planning, signaling an emphasis on clinical translation and manufacturing scalability.

🧪 Wyss Institute at Harvard University

Boston, MA

The Wyss Institute is engineering universal, implantable liver tissue derived from adult stem cells. Their approach focuses on overcoming fabrication limits while enabling continued in-vivo development post-implantation.

🔬 University of California, San Diego

San Diego, CA

UCSD aims to produce patient-specific livers tailored to individual anatomy and physiology. The platform emphasizes long-term integration without donor tissue or immunosuppression.

🏥 University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Dallas, TX

UT Southwestern is pursuing fully transplantation-ready livers, with integrated vascular reconnection and bile duct systems—critical steps toward full physiological functionality.

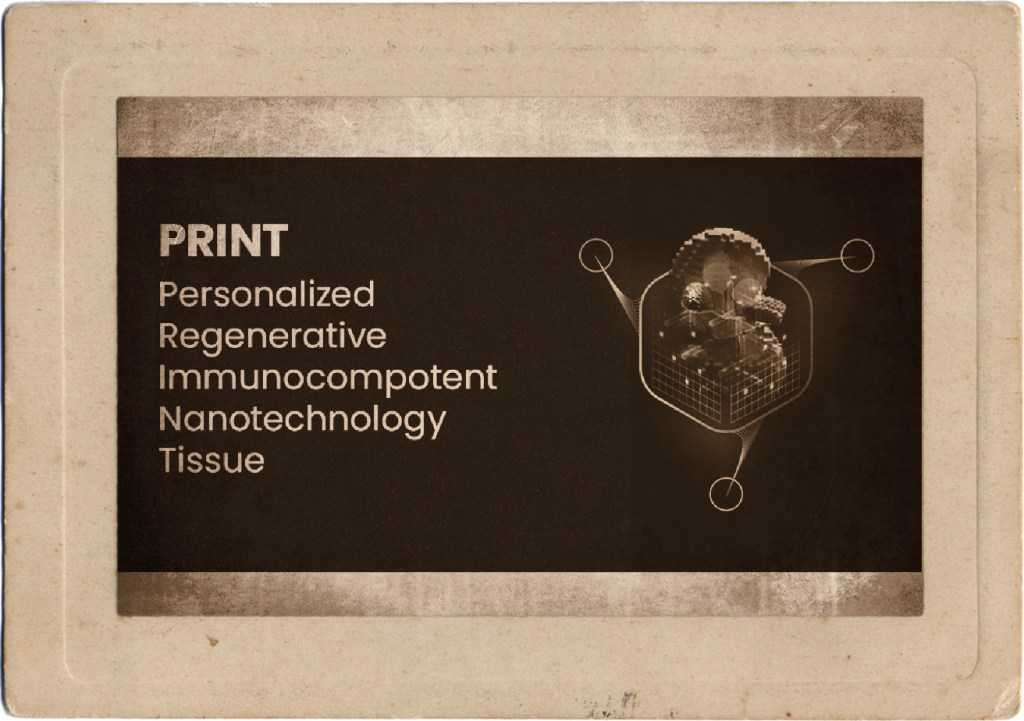

A New Funding Model for Biofabrication

Notably, PRINT awards are structured as performer contracts, not traditional grants. Funding is milestone-driven and contingent on rapid technical progress.

This model reflects ARPA-H’s broader philosophy: fund high-risk, high-reward biomedical engineering at a pace closer to aerospace or defense R&D than academic research.

For biofabrication startups and translational labs, this signals a shift toward:

- Platform-level validation

- Industrialized tissue manufacturing

- Regulatory-ready development

- Aggressive clinical timelines

PRINT is not funding “papers.” It is funding production systems.

Implications for the Bioprinting Industry

If even partial success is achieved, PRINT could accelerate several industry trends:

1. From Tissues to Organs

Most commercial bioprinting today focuses on models, patches, and microtissues. PRINT pushes the field toward full-organ manufacturing.

2. Cell Manufacturing Becomes Central

Scalable, GMP-grade cell expansion and differentiation will become core infrastructure—likely spawning new suppliers and platforms.

3. Bioreactors as Critical IP

Long-term maturation and perfusion systems may prove as valuable as printers themselves.

4. Regulatory Pathways Will Evolve

FDA frameworks for living, printed organs will likely emerge in parallel with PRINT’s progress.

5. Platform Spillover

Technologies developed for liver and kidney may transfer to pancreas, lung, and cardiovascular applications.

In effect, PRINT is building the industrial backbone for regenerative medicine.

Strategic Context: America’s Biofabrication Play

Beyond patient impact, PRINT reflects a broader national strategy.

ARPA-H is positioning the U.S. as the global leader in:

- Regenerative manufacturing

- Advanced bioprocessing

- Translational bioengineering

- Living medical devices

Just as DARPA shaped the semiconductor and internet eras, ARPA-H is attempting to shape the biofabrication economy.

For investors, founders, and research institutions, this is a strong signal: large-scale, organ-level bioprinting is no longer speculative—it is now a federally backed development priority.

The Bottom Line

PRINT represents one of the most ambitious investments ever made in bioprinted organs.

With up to $176.8 million deployed across leading institutions, ARPA-H is betting that coordinated engineering, biology, and manufacturing can finally overcome transplantation’s structural limits.

If successful, the result will not just be better grafts.

It will be a new medical supply chain—where organs are built, not donated.

And for the biofabrication sector, it marks the beginning of a new era: one where printers, cells, and bioreactors converge into true regenerative factories.

Leave a comment